I. Pictures

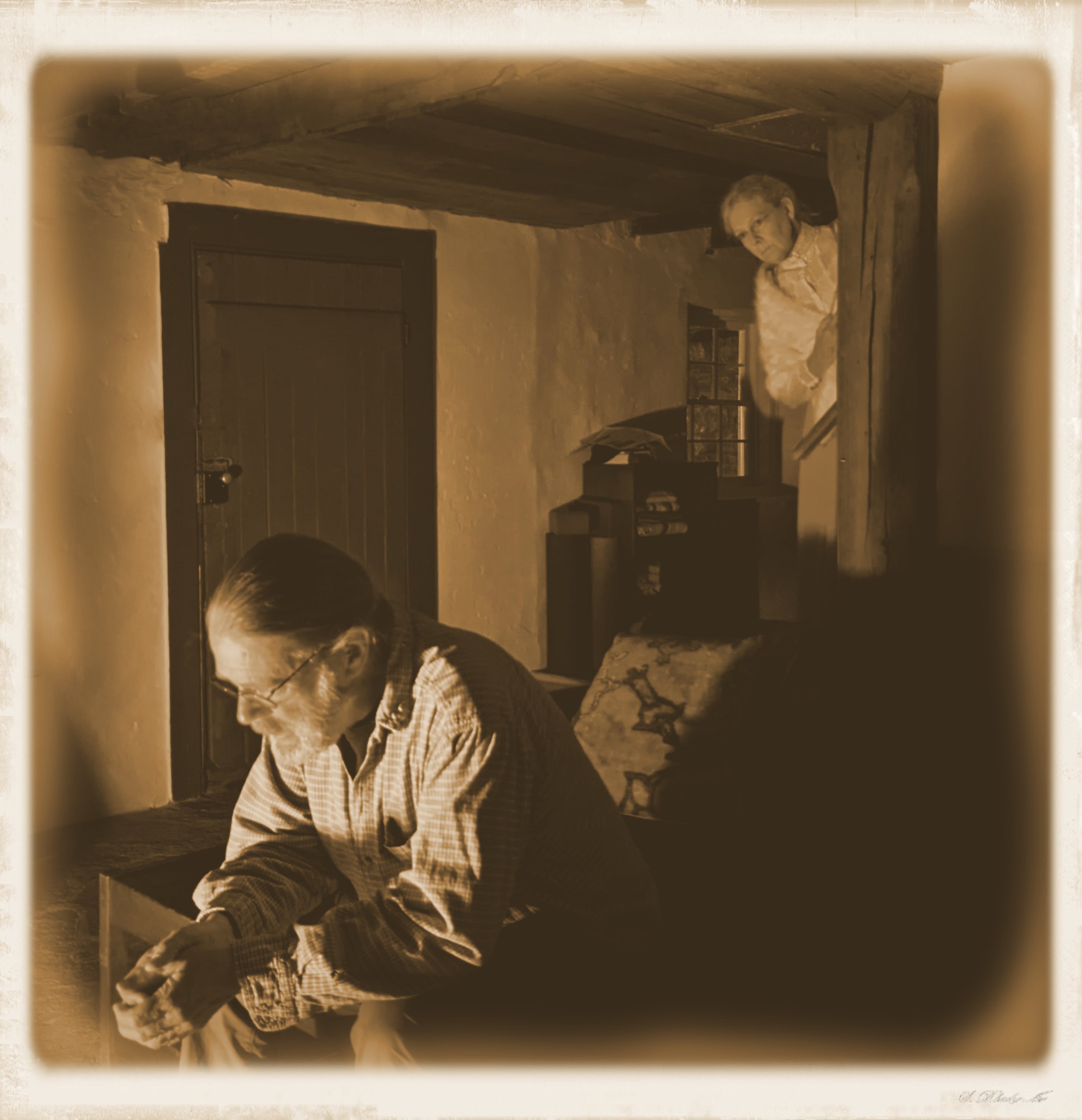

And how were we to know that this was a picture of Ms. Claus? There she was, in plain sight, assessing the tools, captured on a worn picture that had been tucked in the browned, fanned pages of the Dickens classic, A Christmas Carol, which itself was stacked and squirreled away -- a bookmark of sorts -- in the attic at Manor Mill, right here in Monkton. And we nearly breezed right over a line of words penned on a small slip of paper that we now have read over and over, as if new words might show up if we kept staring at it: “What a lovely story!”

For a picture meant to kick off the Christmas season, we recognize that this shot is a stern one. We see Ms. Claus so focused, so intent and determined. She seems to be counting something. But what? Or is she happening upon an answer, her finger tilting a “Wait!” ... as if she too -- she, the very miracle that starts and ends at the North Pole -- stumbled upon enlightenment like the rest of us, at the most unexpected moment?

The second picture, the one with her hands locked behind the small of her back, is equally perplexing. You can almost see the wheels and gears of her mind, turning, not unlike the millworks likely running just beneath her feet.

Boy, there’s a lot more of this story to tell.

II. The Miller

One by one, we rifled through the pictures that were stuck almost randomly in the pages of stacked old books in the attic of Manor Mill. We stopped at this one, which read “1850” in pencil on the back.

We know a good bit about the Merryman lineage in the 1800s in northern Baltimore County, including the fact that John Merryman of Benjamin left Manor Mill to his son John J. Merryman in 1848 and, with a $1000 capital investment, two millstones and one employee, later sold it to Samuel Miller in 1864, 18 years later -- which by no coincidence, is also the period of time that Monckton lost its “C” and became Monkton. Some fine histories have been written about this period, a time of growth and vibrancy when the North Central Railway opened (1832) and was running a full schedule, the Monkton Hotel was built (1858), and all of infrastructure (Town Hall, Saddlery, Blacksmith, and the like) sprouted up like wheat along Monkton Road and the great Gunpowder Falls, which flowed heavily with trout, mink, beaver and of course, passion, south toward the City.

What we don’t know much about, though, is this “one employee”, the Miller, who had to have been very busy. What’s so special about this picture, and how does it relate to the holiday mystery unfolding before us? We’re beginning to answer that.

For now, though, this image captures at a micro level a moment of hard labor and problem solving, but at a macro level, a window into the challenges of industrialization happening in real-time. Just here: how on earth would a lone miller lift an 800-pound solid cast iron axle?

III. An Old Sleigh

For those of us who considered the route Santa Claus would take looking at a deep night sky like this one (taken from the parking lot at Manor Mill with the awfully impressive photography skills of @bollingsr ), it just seemed natural that a sleigh would be the ride of choice. And why not? Darting along at an impractical velocity, the vehicle of choice may not have mattered, except for having good runners for a smooth landing.

In any event, this is important because for anyone who stopped by Manor Mill in the last two years, you probably caught a glimpse of one heap of stuff or another --- barrels of soured cider, palette jacks, a milk tank, buckets of rusty tools, a corn husker, weathered beams, an old motorcycle -- joined, if by anything, by randomness, each with a story to tell. So it didn’t surprise us, really, that among the augers and knee braces, rock maple slabs and mill gearworks, there was a sleigh, of a modest sort but subtly elegant in its simplicity. And, like much of the things we found at the mill, we decided to “wait and see”. And thankfully, we now know why.

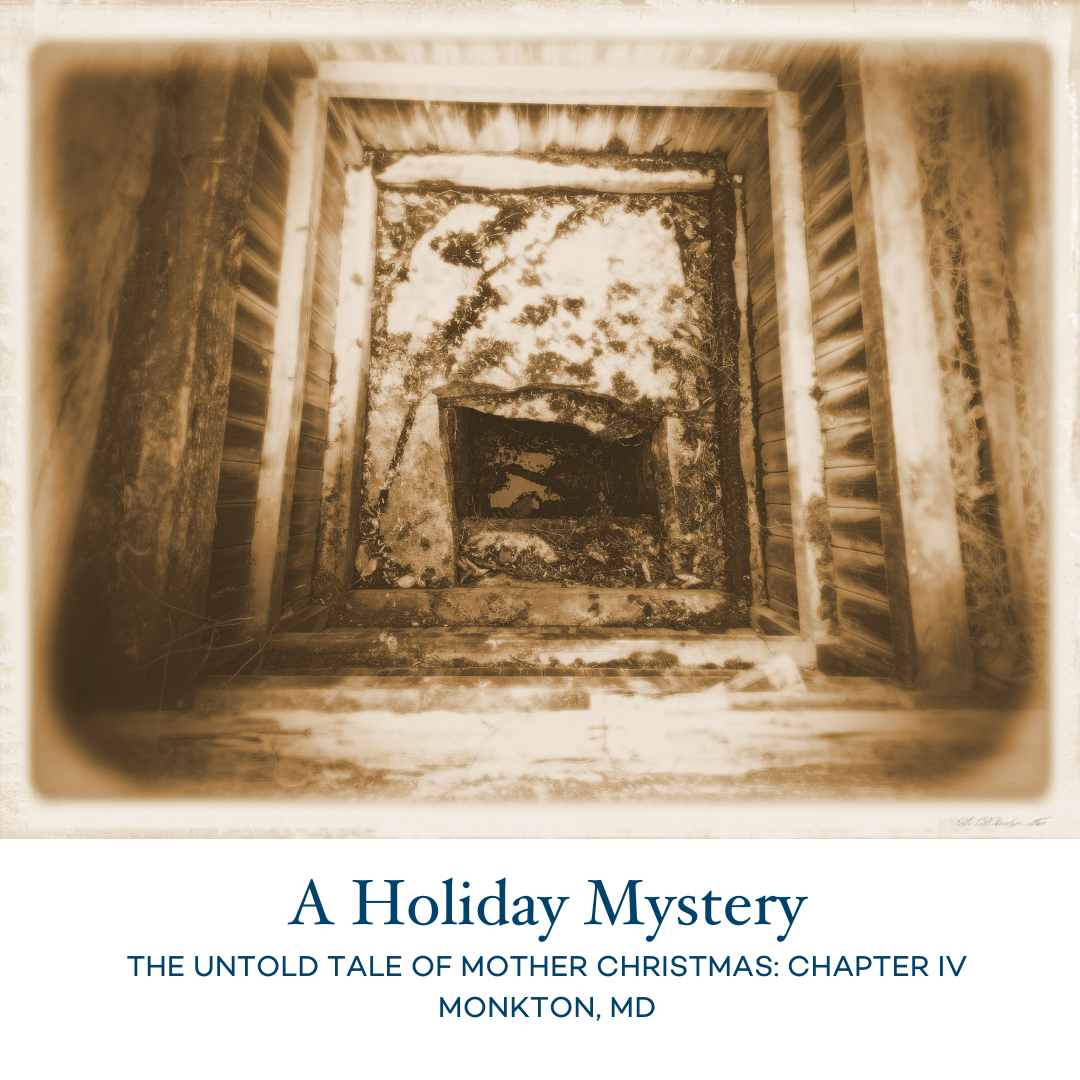

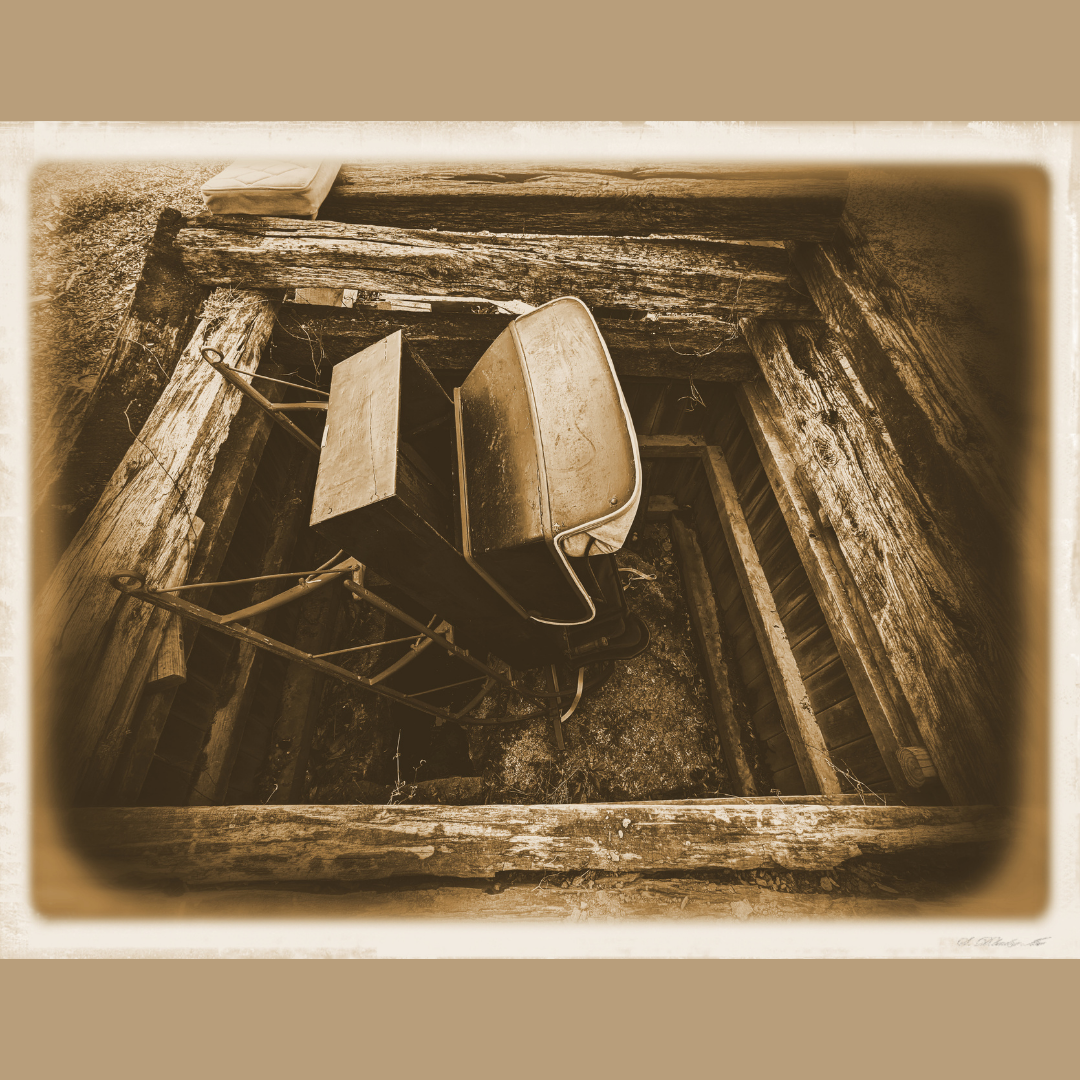

IV: The Pit

Along the unofficial tour of Manor Mill is a stop by what is sometimes unceremoniously described as “the pit”. More precisely, though, it’s an access point, an unexpected (unplanned?) break to the tailrace, which routed the water from the mill out to the Charles Run river once it had done its job moving the 28’ overshot water wheel. The tunnel is built of dry stacked rock with enormous slabs that make up the ceiling, and it is either scary and claustrophobic or beautiful and enticing, depending on one’s perspective on 19th century underground construction. Like many things at the mill, it’s worth seeing for yourself.

It took us a while to realize that this picture we found in the stack of old photos buried up in the attic of Manor Mill was also one of the “pit”. The washed-out light and heavy contrast in the sepia tones felt hypnotic, a kaleidoscope of sorts. Why would someone (the woman in earlier pictures?) from that era go through the trouble of taking a picture of the pit?

And there, on the back of the picture, was carefully written: “Not a chimney!” It was all very puzzling.

V. Consternation

Later on, as we rifled through more stacks of books, we found these two pictures together in the Miller’s House in a high bookshelf.

The first picture, a seeming moment of serenity: Ms. Claus (though at the time her identity was still its own mystery) taking a moment to consider her day. But, combined with the second -- the one of the sleigh face down in the pit -- changes this picture dramatically. Now, she is standing there in a place of quiet alarm, her gloved hand gripping the side of the dresser as if to hold her balance, a passive gaze outside toward the woods now a fretful stare as her mind whirled with options and scenarios. Was that her sleigh? And what was it doing in the pit?

VI: Ornaments

Naturally, when we found these hand-made ornaments in a box up in the attic, we knew they’d be perfect for our first Christmas tree on the second floor of the Mill. And we knew exactly why it had to be on the second floor of the Mill -- because that’s the picture we found of Ms. Claus and the two elves, Merry and Tinsel -- Merry, crouched, poised like a cat as if the ornament Ms. Claus was hanging might fly out of her hands (or simply that the excitement of placing the first ornament was so unbearably exciting that it took every bit of her willpower not to jump on the tree right then and there); and Tinsel, more reserved, helping Ms. Claus find just the right spot.

Which leads us back to the core question at hand: what were two elves and Ms. Claus doing decorating a tree in the Mill in 1852 in the first place?

VII: Landing

And then! We found these. There is only one way to interpret seeing Mother Christmas on the rooftop of the Miller’s House: she landed there.

You may already be one step ahead, thinking: “Hang on, where are the reindeer? The presents? And “the Big Guy”?” All good questions. And we’re gathering answers.

For now, though, most curious to us was the predicament Mother Christmas must have found herself in. Does she knock? And what does she explain on her way in? Why not head down the chimney the old-fashioned way? And what about leaving her sleigh in full view? It had us thinking.

VIII: Alone

We return, now, to the “one employee”, referenced in the documented transaction between John Merryman of Benjamin in which he left his son, John J. Merryman, the Mill in 1848.

We took notice that in the first picture -- the one in which the Miller, the “one employee”, is in the barn, wooden mallet in hand, block plane and framing square in reach -- we could see the mist of his breath, a puff of a smoke fixed in time. For a picture taken in the mid-1800s when a camera needed several minutes of exposure, this meant one thing: it was very cold. And if it was that cold, it also got dark early.

Surely the Miller had his hands full running a three-story grist mill at a time when commerce was booming in Monkton. The 28’ overshot water wheel could easily turn the runner stone at 120 rpm, the wheel’s axle tied to a heavy drive shaft running its way up each floor to power other equipment. This meant there wasn’t much time for “hobbies” and certainly not during the day. Yet here we see him making, building, crafting his own window of possibility, despite every waking minute focused on sacking flour into linen bags.

Which brings us back to Ms. Claus, or Mother Christmas, who might for a moment have been in eyesight of the Miller, stuck as she was on the property (and standing on the porch roof no less); but the Miller was clearly preoccupied. This “one employee,” alone in a mill full of noisy straps and gears, probably had neighbors to help, but they came in the morning and left at night. What we concluded, after a while, was that the Miller was lonely and forlorn, working by himself through a dark and cold winter. The Christmas holiday must have seemed awfully distant that day. And unbeknownst to him -- yet within earshot -- Ms. Claus was having her own bout of mild depression and shots of panic, not about the Miller’s condition, but that Christmas might not make it here at all.

IX: The Traveler

Among the bins of antique tools uncovered at Manor Mill, little did we know that this one, commonly (and befittingly) known as the “traveler”, would be so important to the story of how Mother Christmas would make it home after finding herself unexpectedly grounded on the property at 2029 Monkton Road.

The wheelwright’s traveler is a measuring tool, an ingeniously simple approach to finding the circumference of a wheel or a metal runner. And this one -- forged iron with neatly etched measurements and fastened to a worn wooden handle -- probably sat around on the Miller’s workbench alongside the square, block plane or hand saw, a ready companion in making critical repairs for carriages and sleighs to return them to working order.

We knew at this point that Mother Christmas, or Ms. Claus, needed two things, and needed them fast: to fix her sleigh and to find the person to fix it. As it turns out, this traveler grew much more into its namesake, bridging the divide between reality and that alternate dimension she would need to finish the important job of Christmas in December, 1852.

Though there was more to figure out, the pictures of this story were starting to string together, like lights on a Christmas tree, illuminating the whole.

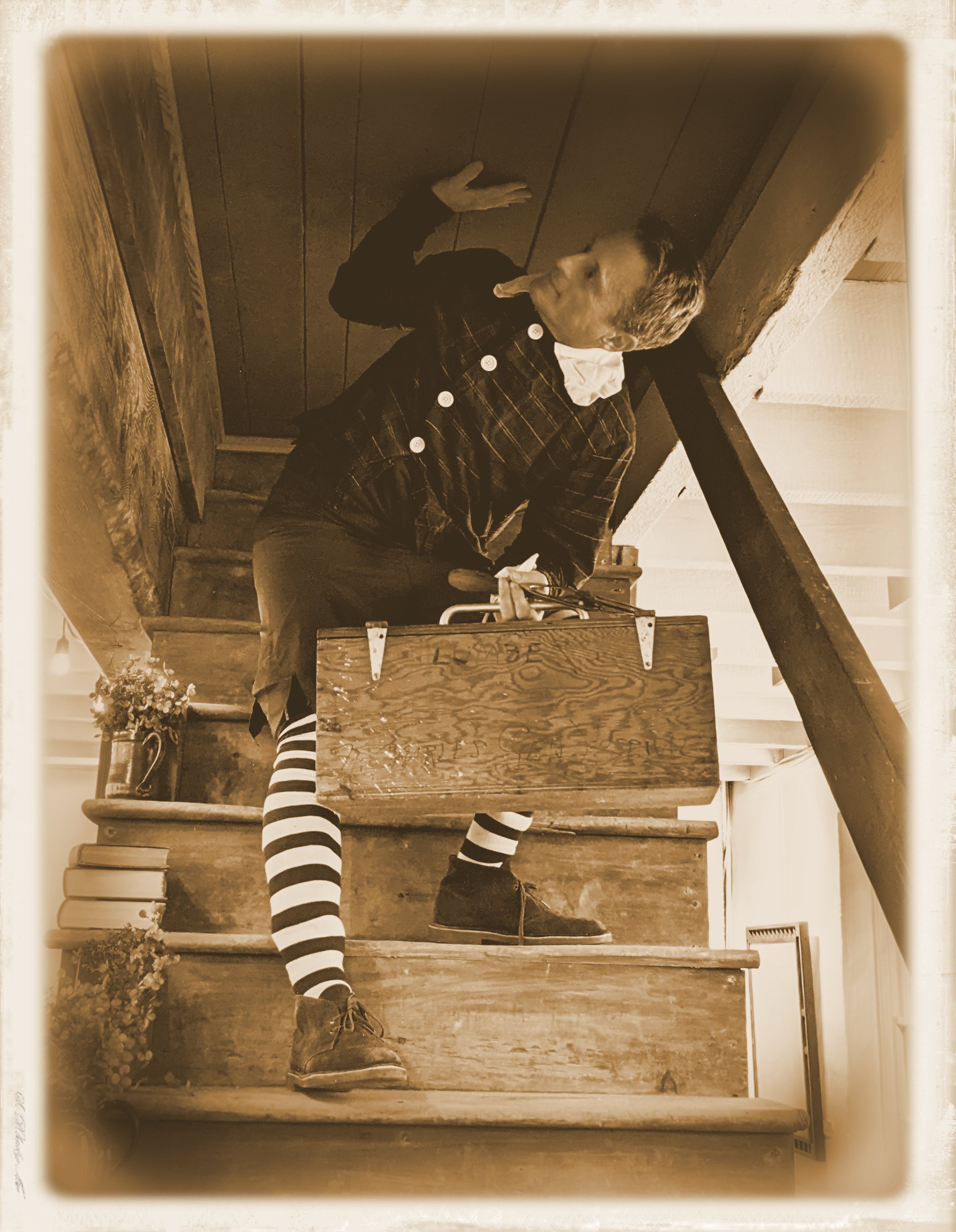

X: Elves

Meanwhile, back in the Mill, the elves, Merry and Tinsel, must have known Mother Christmas was in a deep quandary, trying to cheer her up by decorating a tree, alight with joy, but then at times captured in protracted moments of concern – not a typical sentiment for elves brought to life by Mother Christmas herself. And she desperately needed them to help: the sleigh was broken, and it was stuck, and it had lost its power of flight, and there seemed to be few options at hand. Mother Christmas was without a card to play, the elves unschooled in the physics of sleigh propulsion, and the Miller, awash in the bleakness of the deep winter darkness, seemed to have his hands too full to bag even a gram of her worry.

XI: Quandry

The reality was settling in. Mother Christmas, stuck in Monkton, her sleigh grounded after tailspinning into the pit that led to the tailrace, and then somehow on the porch roof of the Miller’s House – as if her sleigh had sputtered in a fit of animation, before stalling out, and not a reindeer in sight. Here she stares at the sleigh, trying to will it into flight. What was Ms. Claus to do?

XII: Companionship

There are moments we wish we could have witnessed, particularly the one in which Mother Christmas, or Ms. Claus, announced herself to the Miller, having crashed her sleigh down the Mill’s tailrace, then realized she was unexpectedly stuck, an inadvertent trespasser in the middle of trying to throw some joy to the world. So what did she say? And how did she explain her predicament? She from the North Pole, he from Monkton.

Sleighs were a practical transport over snow, so she could have whitewashed her story in a keenly-tied bundle of fabrication, but we think that just wasn’t her style. We also lean toward the notion that the Miller may not have cared, and might rather have welcomed the company without question, a lonely man buried in the depth of winter, just before the solstice, when the nights were longer than the days.

Whatever the case, we know they spent time together, like here, by the fireplace of the Miller’s house, staying warm – she imparting a fresh perspective without boundaries, and he problem-solving a path to her flight. Her grounding somehow allowed him to take off, a 19th century mental boarding pass of sorts. She was anxious to finish her job, and he had a mill to run, but these moments of companionship were quite peaceful.

XIII: Repair

At what point does a sense of wonder become a work of fact? And can a work of fact return to a sense of wonder? A child’s resolute commitment to Santa Claus, a young teenager’s reluctant skepticism about him, and the grownups’ promulgation straddling both – they all run along a continuum from wonder to fact, one tied in a bright ribbon then unraveled by science and practicality (after all, 7.7 billion people is a lot of visits for one night) -- meaning, there’s an end to the Claus continuum and it ends somewhere around age 12.

Which is why to consider this picture of the Miller and a neighbor (whose name we only know as “Jack”) repairing the sleigh that got stuck in the tailrace, that grounded Mother Christmas, and which put the Christmas of 1852 in jeopardy – is to revisit fact and replace it with wonder. The sugar plums, after all, had begun their ascent.

But there in the barn is the Miller alongside a local expert in sleigh repairs, measuring the runner with the wheelwright’s traveler, and that’s where things – in our heads at least – fall apart. What was it about this tool, or the Miller, or his friend, or all three – that could send Ms. Claus back into the sky?

XIV: Alignment

The elf, Tinsel, ferrying a toolbox from the attic of the Mill; the Miller, an eye and a heart for tools and the problems they solve; Jack, the local sleigh expert who arrived at Manor Mill on happenstance, a fount of knowledge at the ready; and the “traveler”, the tool of choice. Like a dated strand of Christmas lights where the bulbs must be firmly in place for them all to stay lit, each of these incidental actors were now connected and dependent upon one another, unknowingly at first but deliberately later. This story started as a mystery, but it was becoming a miracle.

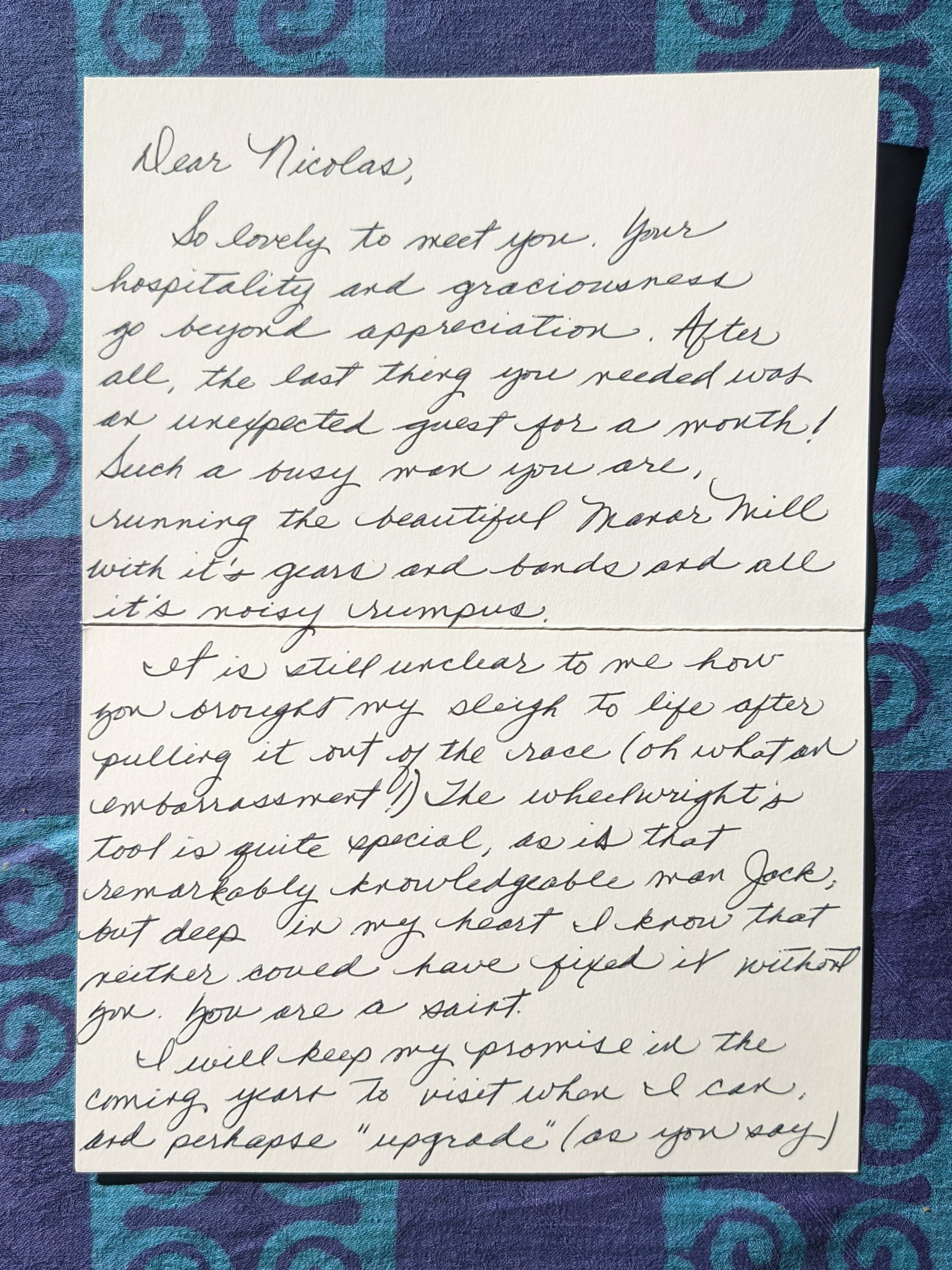

XV: Letter

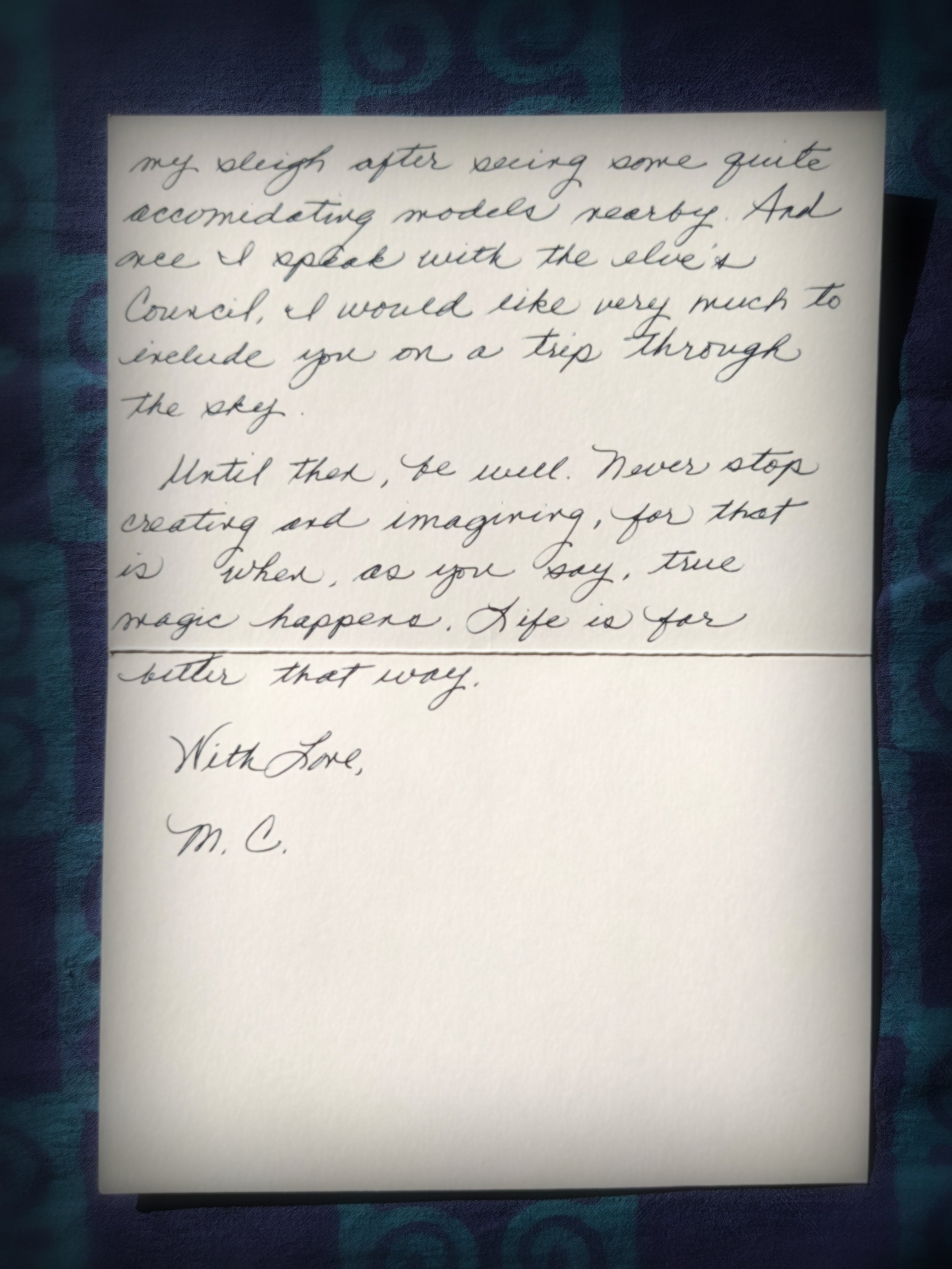

And then, after piecing and speculating, dot connecting and hypothesizing, we found the letter from Mother Christmas to the Miller, another tucked in the books up in the attic of Manor Mill. It read:

“Dear Nicolas:

So lovely to meet you. Your hospitality and graciousness go beyond appreciation. After all, the last thing you needed was an unexpected guest for a month! Such a busy man you are, running the beautiful Manor Mill with its gears and bands and all its noisy rumpus.

It is still unclear to me how you brought my sleigh to life after pulling it out of the race (oh, what an embarrassment!) The wheelwright’s tool is quite special, as is that remarkably knowledgeable gentleman Jack, but deep in my heart I know that neither could have fixed it without you. You are a saint.

I will keep my promise in the coming years to visit when I can, and perhaps “upgrade” (as you say) my sleigh after seeing some quite accommodating models nearby. And once I speak with the elves’ Council, I would like very much to include you on a trip through the sky.

Until then, be well. Never stop creating and imagining, for that is when, as you say, true magic happens. Life is far better that way.

With love,

M. C.”

XVI: Departure

The elves, in a breathless, worried moment, watched the sleigh jostle, as if along a bumpy road, and then with a burst of acceleration, Mother Christmas was up into the sky, a shot in the dark. The sleigh had been fixed, and Christmas had been saved.

She looked back and waved slowly at Tinsel and Merry, who were paired up inside; the Miller, who stood outside nervously watching things unfold; and Jack who held the Traveler in his hand. They waved back, and with that, Mother Christmas was gone.