Interview with Penn Eastburn

By Katie Aiken Ritter

It’s pretty cold in Penn Eastburn’s studio; not quite freezing yet, but he’ll be working through the night, and it’s going to get a lot colder. If Penn can stand it, so can I. I pull my hat down tighter and watch him work.

Behind Penn, framed by a wide-open barn door, sprawls a plein air artist’s dream landscape: a field and naked misty winter trees backed by a sky of the softest pink. Dusk approaches; it’s lovely. But Penn’s attention is on the huge canvas in front of him: grays, blacks, whites and shades of silver connect with old fabric, with paper, with long-ago photographs and random openings. Penn works on abstract pieces, and they are, in a word, complex.

“Abstract art can make people nervous,” I say. “Especially very complex pieces. Nobody likes to seem stupid, so lots of folks lump abstract art into an ‘I don’t get it, moving on’ bucket. But it helps if they can have a way into the piece, some understanding of where it starts, how it happens…a bit of what might be the idea behind the piece.”

For me to serve people who view his art, Penn has to help me understand his evolution as an artist—and he does, with gentle grace.

An abstract artist’s journey is often as complex as their work. For Penn, the first steps meant studying film and media at college in Utah followed by jobs he describes as ‘art-adjacent’: working in a custom frame shop, working as an artist’s assistant in Brooklyn, working at a contemporary arts center in Jersey City—and now, working as an art handler in New York. As Penn talks, he keeps working on the huge tonal piece between us, the elements of it seeming to take and give quiet energy between themselves.

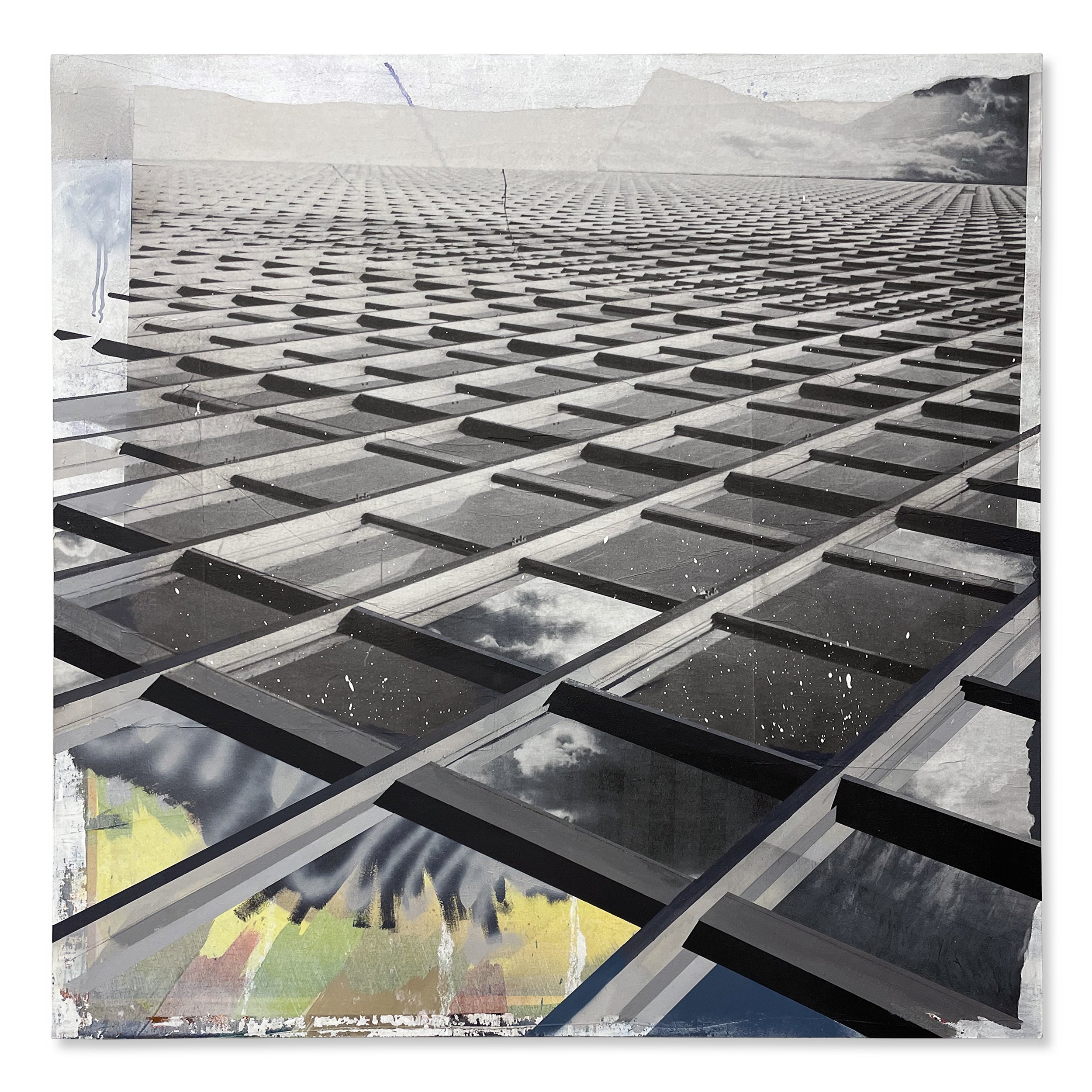

Attachments by Penn Eastburn

“What’s an art handler?” I questioned. “Asking for a friend.”

Turns out that being an art handler forms a perfect introduction to the world of highbrow New York art: someone who drives a truck, transporting artworks to a gallery or museum or collector’s home, and hanging contemporary art of all forms. It means being around people who make their living from art—and gradually, the idea of choosing art as a career began to grown in Penn.

Studio practice started in a bedroom apartment, then moved to a small (“legitimate,” Penn says) space—and from there, to larger and larger spaces that could accommodate bigger works. His dedicated studio practice eventually led to an MFA program at the Hoffberger School of Painting at MICA.

That brings us here, to a cold evening that’s getting colder, and a piece of abstract art that is mysterious and subdued, brimming with texture, and offering an intriguing invitation: to look, to respond, to wonder…to engage.

Penn works with found materials: leftover screen door mesh and unused fabric samples. Spray paint and house paint, oil paint and acrylics.

He works with ideas that can have double meanings: Nothing is Enough…or Nothing (actually) IS Enough.

A repeating element for Penn is using cut-up reproductions of intriguing old photographs: gelatin silver or platinum photo prints from the late 1800’s to early 1900’s. Penn finds these mysterious and often haunting images in photo archives—free and in the public domain—and prints them in super-scale at a DIY printer at Fedex.

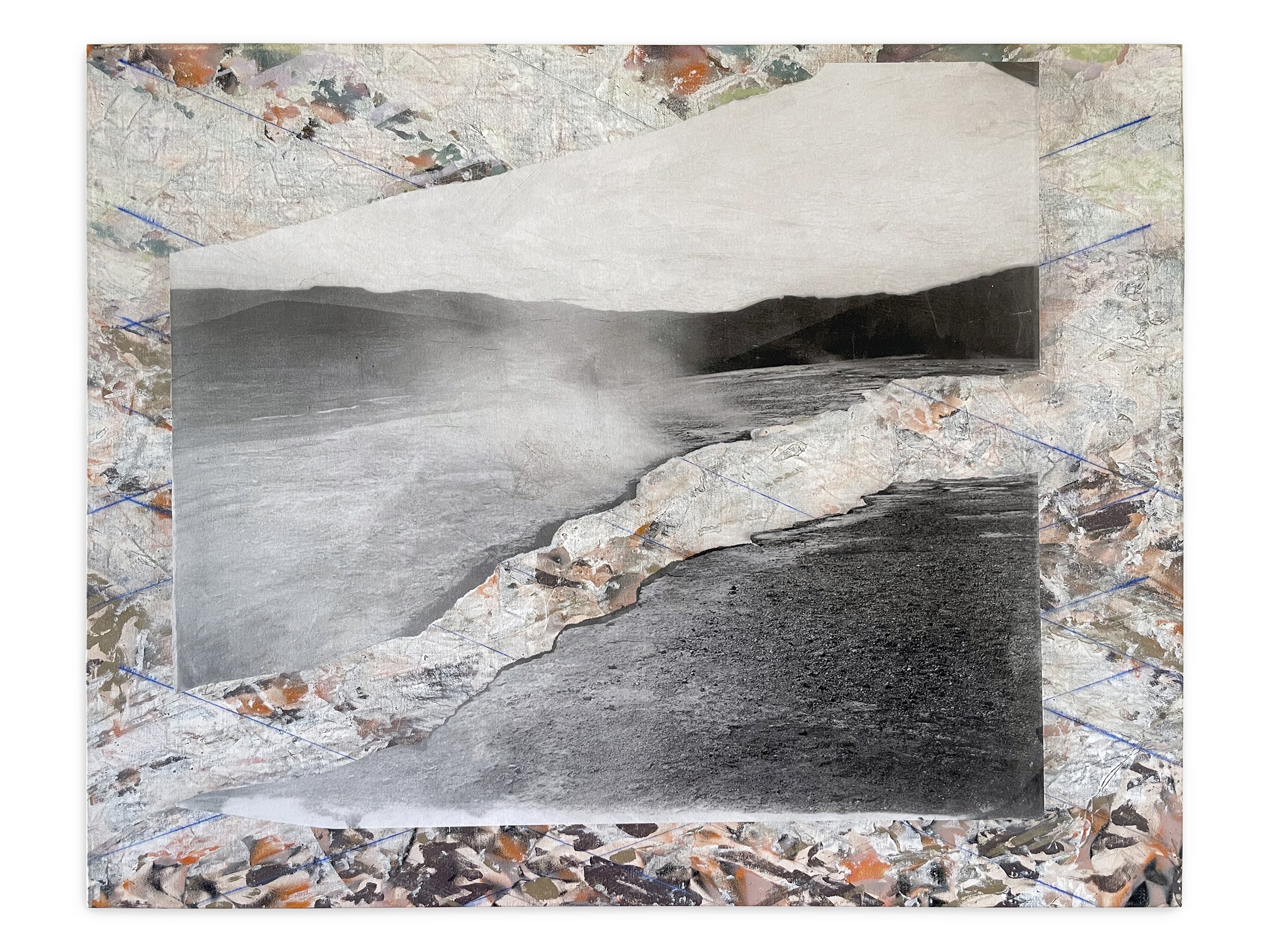

Retrograde by Penn Eastburn

He works with patience and time: waiting, discerning, paying attention to a particular thought that comes while he’s working, and considering how it can fit into the space of the canvas. If a person is in the image, considering what might he or she be looking at and thinking about. Thinking of the past, the future, the way things in the painting extend out into the world. It takes time for such subtle interactions to develop.

But most of all, in each piece of art Penn creates, he works with space. You’ll find unexpected openings, empty spaces, areas cut out of those large-scale vintage photographs. It makes for window to look through, creates voids to be filled—with what you sense coming from within your own being.

Openness, Penn says, is really, really important to him. It is why he likes to begin with emptiness, to start by pulling things out of the emptiness—and he enjoys being surprised by what comes.

Like a kid’s Lego table, he says. Square, ready for something to be built—and in the center, an opening: a net pocket filled with pieces to use. From that opening, in the process of building, the idea takes shape, grows, changes, and finds unexpected forms.

Such a simple analogy, but we get it.

And it works. I still may not fully understand his work, but Penn’s pieces inexorably draw one in, evoking enigmatic hope, or longing. Of beginnings, or of movement.

And somehow, our own reactions become part of what is happening. Flowing inward and outward in every direction—and across time as well—those mysterious silvery images of forgotten people, places and things evoke a sense of wondering, of yearnings experienced long ago—and invite our own wondering and yearning, for what was, what is, what may be.

“Wherever you are is at the center of everywhere that you are not. Wherever you are, right now, is at the center of every single possibility of past, present, and future,” Penn says. This complex, wonderful concept gives title to this show: AT THE CENTER OF EVERY DIRECTION.

Penn gives himself time to let the relationships of each element in his paintings evolve. It’s a quiet, organic process, much like Penn’s exploration of art in his own life.

Threshold by Penn Eastburn

“I like to give things time to unfold at their own pace,” he says. “I’d like to show more, but I’m not really in a rush to blow up or anything.” He’s calm, measured, organic, quiet, introspective, and—like his artwork—a genuine pleasure to be around.

Penn keeps working. The dusk deepens. It gets colder. I’ll soon head home, but he’ll be out here in the barn studio working all night, finishing pieces for this show; letting ideas interact, letting energy ebb and flow, in and out, back and forth, everything connected.

What Penn does not realize is that behind him, from where I sit, the barn door stands wide open. A void, unobstructed, just like the ones he cuts out of his paintings; an opening from which anything can come. Penn is concentrating on his canvas, not realizing that—just as in one of his paintings—his life and his work stand framed by openness, here in a quiet barn in the middle of rural Monkton. Here…at the center of every direction.

Penn Eastburn’s exhibit is at the Manor Mill, a laid-back gallery in an historic grist mill, from February 4 to February 26. For added inspiration, the Mill is hosting At The Center of Food and Art, a celebration of fine art and fine food featuring comments by Penn and fellow artist Emma Childs on February 18. Click here for tickets.

By Katie Aiken Ritter

Instagram: @KatieRitterVikingWriter

Contact

gallery@manor-mill.com

Instagram: @manormillgallery